Nerve transfers as a window into the capacity for human sensory adaptation

Let’s imagine that in a hypothetical future world, head transplants become possible, as somehow the massive technical challenge of reattaching the brain to the spinal cord can be overcome. This would raise an empirical question: is your brain able to adapt to the novel sensory inputs?

An analogous question, probably even more distant in the future but more relevant to the BPF, is whether sensory adaptation could also occur following brain preservation and mind uploading.

Personally, I consider this a relatively small and straightforward step relative to the other massive challenges involved in brain preservation and mind uploading, because we already know about the brain’s high degree of plasticity from many lines of evidence, such as sensory map reorganization following digit amputation and remapping of brain areas to auditory sensation following visual loss. Given enough time, our brains ought to be able to adapt to novel sensory inputs.

That said, I remain on the lookout for other examples of brain plasticity and its limitations, because it’s such a counter-intuitive phenomenon. So I was pleased to recently learn about a particularly nice example that’s already in routine clinical use: nerve transfers.

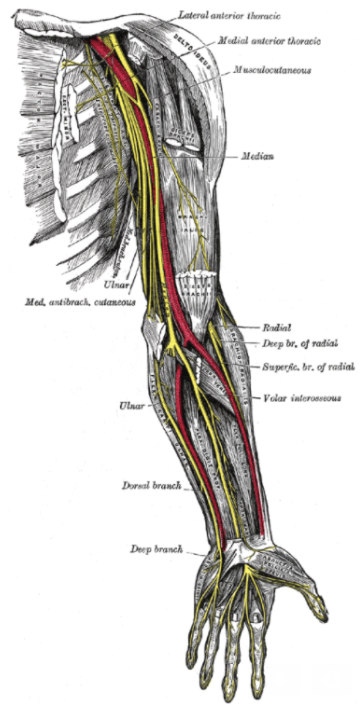

A standard treatment for nerve injury in the past has been nerve grafting, where part of a nerve is taken from a different part of the body (such as the sural nerve in the ankle) and transplanted into the region with the injury. The nerve graft acts as a conduit to allow axons regrowth. But this does not always work, in part because axon regrowth is limited and finicky.

Instead of a nerve graft, nerve transfers involve redirecting part of a healthy nerve into a nearby damaged nerve in order to restore nerve conduction to that region. You can think of it as “plugging in” your healthy nerve to the region with the injured nerve.

After this procedure, you initially control the “plugged in” damaged muscles by activating other muscles that the donor nerve controls. For example, if the donor nerve controls breathing and it was transferred to help part of your arm move, then you can move that part of your arm by taking a deep breath. Eventually, recipients of nerve transfers learn to distinguish between the two motor areas and can control them independently without needing to use any “tricks.”

While it may be an unconventional comparison, to me nerve transfers are another proof of principle that cognitive remapping to novel sensory inputs would be possible after a head transplant or mind uploading.

If you know of any other examples of brain plasticity that you find interesting, we’d love to hear about them in the comments.